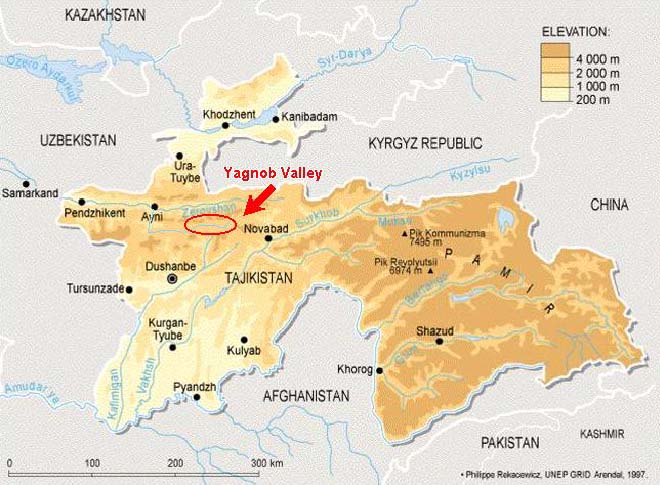

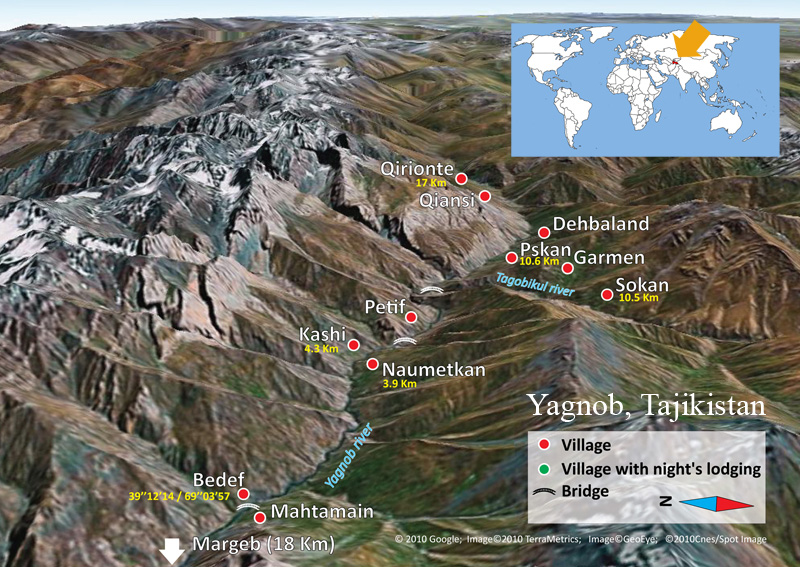

In secluded valleys, words endure beyond screens, whispered between generations in lullabies, blessings, and traditions tied to the land. The Yaghnobi language, spoken in a valley in northern Tajikistan, has persisted through historical turmoil, yet its future remains precarious.

Linguists classify Yaghnobi as “endangered,” a term that fails to convey the profound loss incurred when a language’s unique vocabulary, tied to specific cultural contexts, fades. It also overlooks the remarkable resilience of a people who continue to speak the legacy of ancient Sogdiana.

This exploration delves into the multifaceted meaning of language endangerment, examining not just numbers but also the vital roles of memory, community, and cultural continuity. It raises a crucial question with universal significance: why should we value the voices of linguistic minorities?

Defining “Endangered”

The label “endangered language” sounds simple, denoting a language with few speakers, but it encapsulates a deeply human narrative. UNESCO assesses language endangerment by several criteria, with intergenerational transmission—whether the language is passed to children—being paramount. For Yaghnobi, most children now primarily speak Tajik or Russian, with Yaghnobi often reserved for family stories, rituals, or private conversations, and fewer young people feel comfortable using it publicly. The language’s presence in schools, government, and media is minimal, leading to its shrinking use without formal support. What persists is due to dedicated individuals: elders who continue to sing, narrate, and advise in Yaghnobi, and scholars like Robert Gauthiot, Khromov, Shokhumorov, and Muller, who recognized its value not as a relic, but as a vital link to the past.

Why Do Languages Disappear?

Languages don’t disappear because they are inherently weak, but rather because the surrounding world transforms at an accelerated pace. The allure of urban life draws families away from their ancestral villages. Educational institutions prioritize national or global languages, official documents are drafted in a singular tongue, and media outlets predominantly promote a single language. Consequently, the ‘home language’ gradually becomes restricted to the domestic sphere, eventually receding into memory. The Yaghnobi experience is not an anomaly. In New Zealand, the Māori language faced near extinction before a revitalization movement commenced in the 1980s. Similarly, Basque was once prohibited in educational settings and public life in Spain. In northern Scandinavia, the Sámi people were informed that their language was not ‘civilized.’ These historical accounts resonate with one another, underscoring that language erosion is intrinsically linked to identity, dignity, and historical narrative, not merely vocabulary. Within Soviet Central Asia, the drive for uniformity often led to minority languages being relegated to the status of ‘dialects,’ their literary contributions disregarded, and their schools shuttered. Even well-intentioned literacy initiatives typically assumed that proficiency in Tajik or Russian would suffice, but this was an inadequate approach, as it always is.

What We Lose

When a language vanishes, we lose more than grammar; we lose a unique way of perceiving the world. Ancient agricultural knowledge, encoded in proverbs such as the Yaghnobi sayings about planting before frost or awaiting mountain winds, disappears. We also lose ecological awareness—which plants are healing, which rivers flood, and which animals signal danger—along with rituals, healing chants, lullabies, jokes, and prayers. Memory is also lost. Yutaka Yoshida’s work on Christian Sogdian text fragments unearthed in China demonstrates the former culture’s complexity and far-reaching influence. The remarkable persistence of echoes from this very tradition in the Yaghnob Valley today is extraordinary. Thus, the Yaghnobi language is not simply a repository of old words but a living archive of Central Asian history, held not in books, but in the very breath and memory of its few thousand speakers.

The Value of Minority Voices

Why should this concern us, especially those far removed from Central Asia? Because every language offers a distinct lens through which to view the world, possessing its own inherent logic, cadence, and aesthetic. Allowing a language to vanish signifies a dismissal of diverse ways of understanding. Minority voices are crucial to our collective human heritage, offering alternative perspectives and challenging dominant narratives. They remind us that history is not solely recorded in governmental decrees but is also woven into the fabric of everyday life—in homes, on farms, and along ancient trails. In the Yaghnob Valley, this history still resonates, albeit softly.

Looking Ahead

The subsequent posts in this series will examine the parallel struggles of communities like the Sámi of Scandinavia, the Māori of Aotearoa, and the Basques of Spain and France, highlighting how their language preservation, revival, and celebration efforts offer crucial lessons for the Yaghnobi today.

If history has taught us the vulnerability of languages to suppression, then these accounts also illuminate their resilience and capacity for reclamation.