The impact of isolation, conquest, and survival in the high valleys

Introduction: Where Time Stood Still

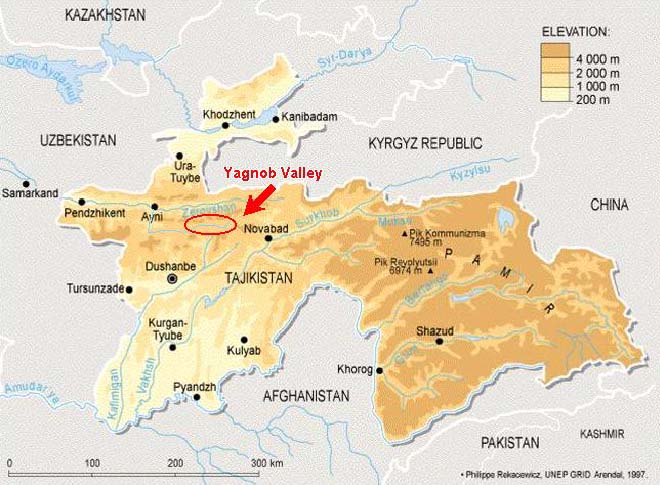

High in Tajikistan’s northern mountains, the Yaghnob Valley was a place seemingly untouched by modernity. Hidden for centuries, its villages were accessible only via treacherous paths, shielded by winter’s heavy snows. Here, the Yaghnobi people created a unique way of life, their culture, language, and identity molded by their profound isolation.

I. Geography as Fate: The Valley’s Natural Fortress

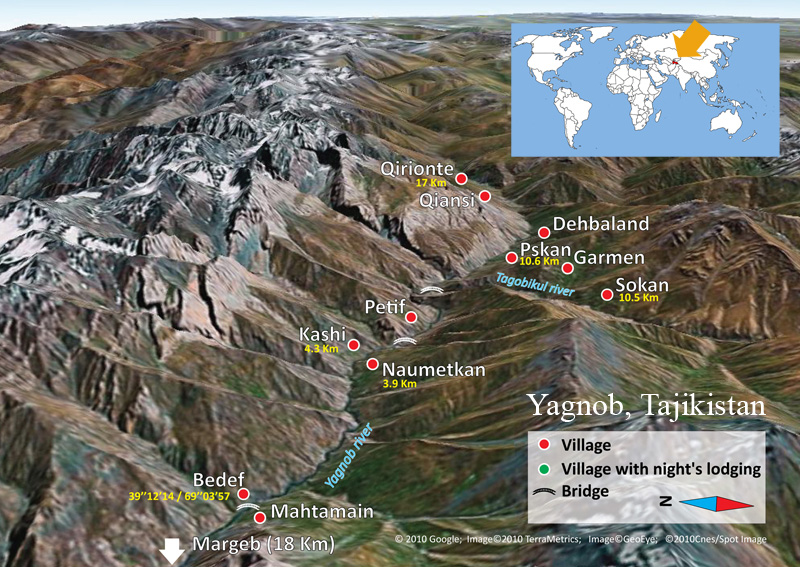

The Yaghnob Valley, stretching nearly 100 kilometers along the Yaghnob River, is guarded by the towering Zarafshan and Hissar ranges. Its deep gorges and dramatic cliffs, reaching altitudes of 2,000 to over 3,000 meters, have long served as both refuge and barrier. Heavy snow and raging rivers made the valley virtually impenetrable for much of the year, limiting outside contact. Villages clustered on mountainsides, linked by footpaths often buried by avalanches. The nearest market towns were a day’s journey away, and harsh winters could isolate entire communities for weeks. This formidable geography dictated every aspect of Yaghnobi life, from agriculture to social structures.

II. A Separate Existence: The Pulse of Yaghnobi Life

- Seasons of Survival

Life in the Yaghnob Valley revolved around the seasons, demanding resilience and teamwork. Spring was a season of hope and labor, as villagers prepared terraced fields and maintained intricate irrigation systems fed by mountain streams. By early summer, families migrated with their herds to high pastures, tending sheep and goats. Autumn’s harvest brought the community together to gather wheat, barley, peas, and fruits, preserving them for winter. Food preservation was a communal effort. Winter was a time of endurance, spent in sturdy stone and wood homes, with livestock sheltered nearby for warmth.

- Village Organization and Mutual Aid

In the harsh Yaghnob Valley, unity wasn’t just good—it was crucial. Villages functioned like big families, respecting elders as keepers of knowledge. Conflicts were resolved by community councils, and everyone pitched in to fix things, from roofs to irrigation. Families were connected across villages through marriages and celebrations. Even Yaghnobis who left to trade or work still felt deeply connected to their mountain home.

III. Culture in the High Valleys: Tradition, Ritual, and Memory

- Faith and Ritual

Over generations, Yaghnobi traditions mixed old beliefs with Islam. While Sunni Islam became the main religion, hints of older customs remained in festivals and stories. People prayed to both Allah and the spirits of nature and ancestors. Special trees, shrines, and natural spots were used for worship and gatherings. Celebrations like Navruz filled the valley with music and dance. Weddings, births, and funerals were big events with traditional songs, poems, and blessings in the Yaghnobi language.

- Oral Tradition and Language

Because they were cut off from the outside, Yaghnobis passed down their history and wisdom through stories. Tales of heroes and ancestors were shared on winter nights. Wise sayings guided daily life and settled arguments. The Yaghnobi language thrived, becoming the main way people communicated. Each village had its own unique way of speaking and telling stories, and everyone took pride in their language. Even when people learned Tajik, Uzbek, or Russian for business, Yaghnobi stayed the language of home and heart.

IV. Resourcefulness in the Face of Scarcity: Survival on the Margins

- Ingenious Farming in the Mountains

With minimal flat terrain, the Yaghnobi people became experts in terrace farming, erecting stone-supported fields on precipitous slopes. These terraces were watered by irrigation systems, some centuries old, demonstrating a sophisticated grasp of water conservation. They grew hardy grains and legumes, specially adapted to the brief growing seasons, alongside fruit trees like apricot, apple, and mulberry, carefully cultivated in small orchards. These fruits were vital for sustenance and commerce. Traditional wisdom encompassed animal care, herbal remedies, and building methods designed for earthquake-prone areas. Weaving, pottery, and woodworking blended practicality with artistry, featuring unique patterns and motifs passed down through generations.

- Strategic Isolation and Limited Engagement

Despite their relative seclusion, the Yaghnobi people weren’t entirely detached from the outside world. Traveling merchants, Sufi mystics, government representatives, and, later, explorers and scientists occasionally ventured into the valley. The Yaghnobis selectively embraced new tools, crops, and concepts, adapting them to their way of life while often resisting external control. This delicate equilibrium allowed them to adopt useful innovations without sacrificing their cultural identity. For most, however, the mountains remained both protection and constraint—a deliberate choice to preserve values of cooperation, respect, and reverence for nature.

V. The Valley’s Contradiction: Permanence and Evolution

Throughout much of its history, change in the Yaghnob Valley unfolded slowly. The valley functioned as a living museum, safeguarding not only language and customs but also enduring landscapes, architecture, and collective memory. Early 20th-century visitors were struck by the survival of ancient words and social structures, which served as tangible links to a Central Asian past that had largely vanished elsewhere. Yet, even in this isolated haven, change was unavoidable. As roads improved and political boundaries shifted, the valley’s isolation became increasingly vulnerable. The arrival of Russian and Soviet expeditions marked a new epoch, bringing both attention and disruption, and paving the way for the profound transformations of the late 20th century. These ventures meticulously recorded Yaghnobi traditions, compiled linguistic data, and mapped settlements. Subsequently, Soviet linguists verified that Yaghnobi retained core elements of ancient Sogdian, igniting renewed interest in linguistic documentation and preservation.

Conclusion: Resilience in the High Valleys

Life in the Yagnob Valley was perpetually challenging, yet profoundly meaningful and interconnected. For centuries, the mountains sheltered a community whose identity was shaped by collaboration, heritage, and language. Isolation, rather than a disadvantage, became a catalyst for resilience and innovation. Reflecting on this era of Yaghnobi history, we recognize not just a world set apart but also a world offering invaluable lessons for all who cherish the bonds between place, culture, and the enduring power of community.